When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how does the FDA make sure that’s true? The answer lies in bioequivalence-a scientific standard that proves a generic drug behaves the same way in your body as the original. It’s not about matching ingredients on paper. It’s about matching what happens inside you.

What Bioequivalence Really Means

Bioequivalence isn’t a vague promise. It’s a precise, measurable standard defined by the FDA in 21 CFR § 320.1. It means there’s no significant difference in how fast and how much of the active drug enters your bloodstream when you take the generic compared to the brand-name version. This isn’t about taste, color, or packaging. It’s about the drug’s journey-from swallowing to absorption to reaching the target site in your body.

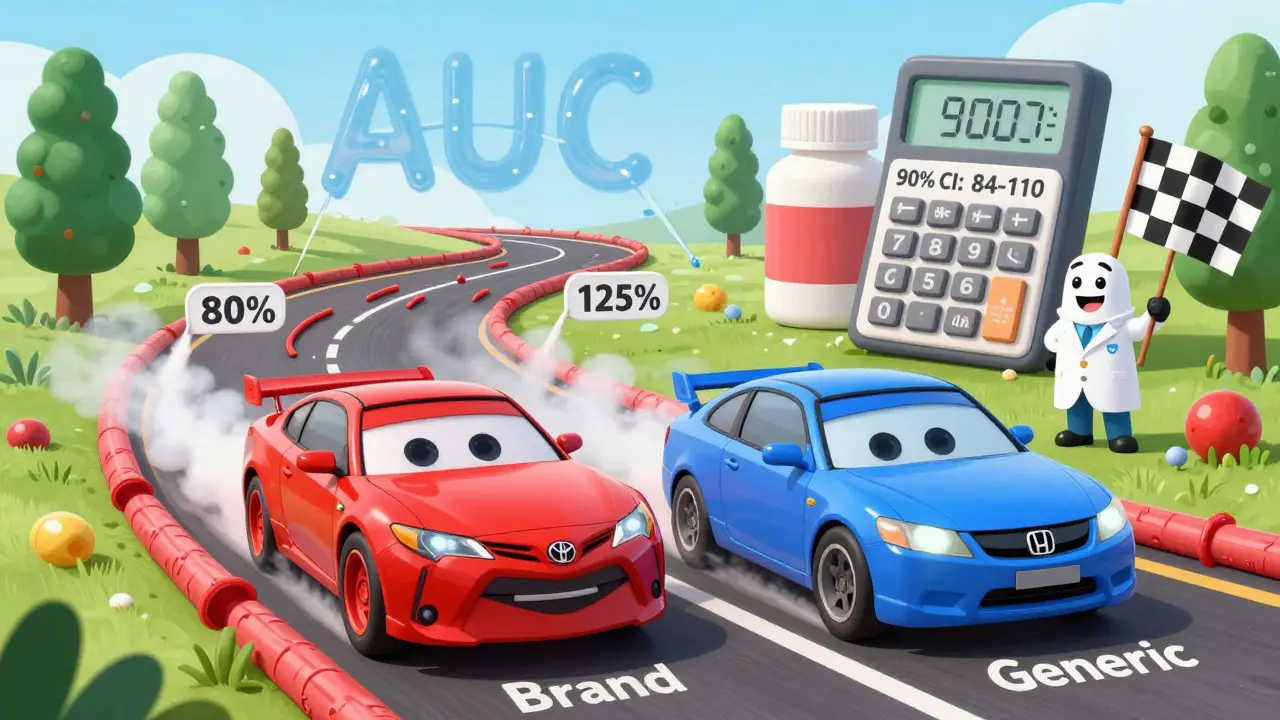

Think of it like two cars driving the same route. One is a Toyota, the other a Honda. You don’t care if they look different. You care if they get you to the same destination at the same speed, using the same amount of fuel. Bioequivalence is the fuel efficiency and speed test for drugs.

The Science Behind the Test

To prove bioequivalence, manufacturers run clinical studies with 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. These are crossover trials-each person takes both the brand-name drug and the generic, at different times, with a washout period in between. Blood samples are taken over hours to track how the drug moves through the body.

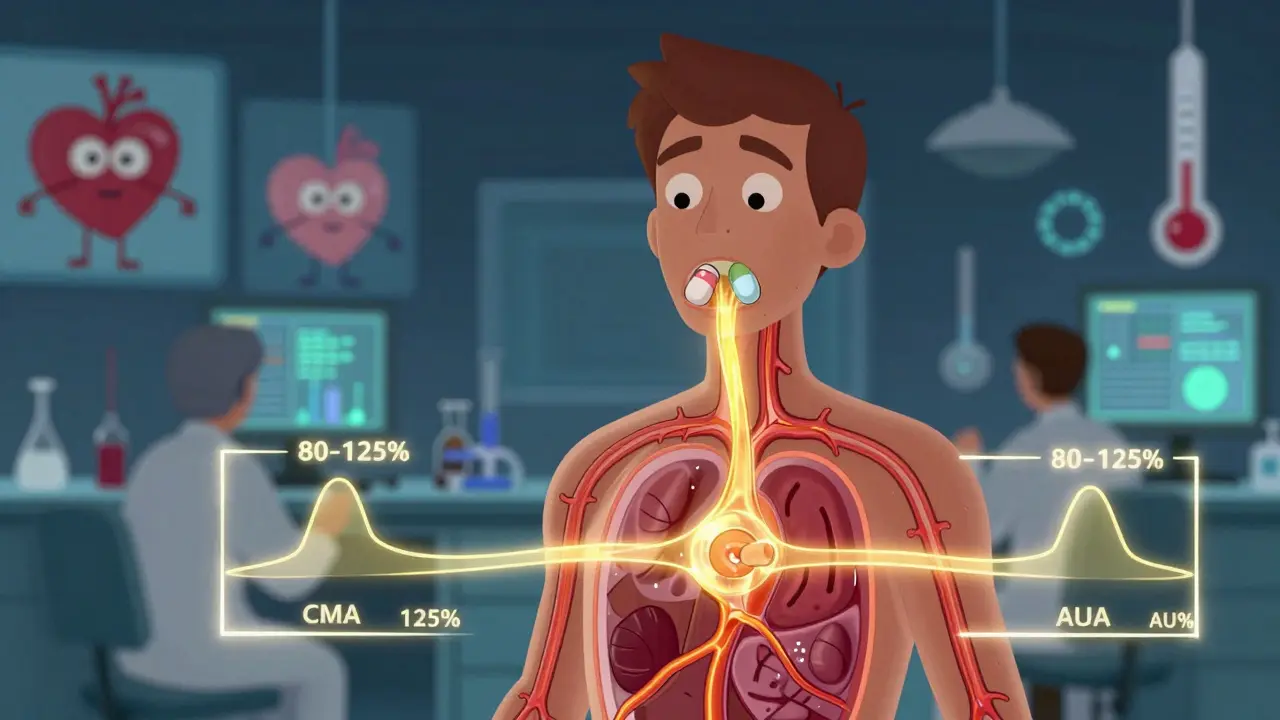

Two key numbers are measured:

- Cmax: The highest concentration of the drug in the blood. This tells you how fast the drug is absorbed.

- AUC: The total exposure over time-how much of the drug gets absorbed overall. There are two types: AUC(0-t) for the time period measured, and AUC(0-∞) for the full estimated exposure.

The FDA doesn’t just look at the average values. They require the 90% confidence interval of the ratio (generic/reference) for both Cmax and AUC to fall between 80% and 125%. That means if the brand-name drug gives you an AUC of 100 units, the generic must produce an AUC between 80 and 125 units for the majority of people in the study.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

- Brand AUC: 100 units

- Generic AUC: 93 units (mean)

- 90% confidence interval: 84-110

This passes. Even though the average is 93%, the entire range (84-110) stays within 80-125%. But if the confidence interval were 103-130%, it would fail-even if the average was 116%. The upper limit breaks the rule.

Myth Busting: It’s Not About Ingredient Amount

A lot of people think the 80-125% range means the generic can contain 20% less or 25% more of the active ingredient. That’s wrong. The active ingredient amount in both pills must be identical. The 80-125% rule applies only to how your body absorbs and uses that ingredient-not how much is in the tablet.

Imagine two identical pills. One is made by Pfizer, the other by Teva. Both contain exactly 50 mg of lisinopril. But if the Teva pill dissolves slower because of its coating, your body might absorb only 85% of the drug compared to Pfizer’s. That’s not a problem-unless the absorption drops below 80% or spikes above 125%. The FDA’s test catches that.

When the Rules Get Tighter

For most drugs, 80-125% is enough. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, lithium, or certain anti-seizure meds-small changes in blood levels can cause serious side effects or treatment failure. Even though the FDA hasn’t changed the official range for these, they scrutinize these applications more closely. Manufacturers often submit extra data to show consistency across populations and conditions.

Some drugs don’t even need blood tests. Topical creams, inhalers, or eye drops that act locally (not absorbed into the bloodstream) can be approved using lab tests that measure how the drug releases from the product. For example, a generic asthma inhaler must release the same amount of albuterol in the same pattern as the brand, even if no blood sample is taken.

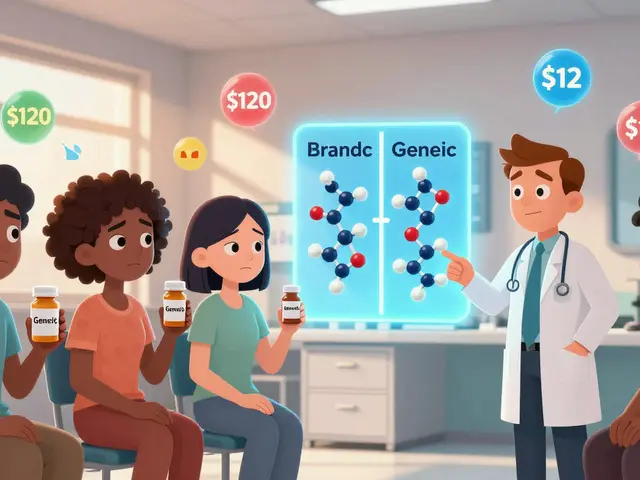

The ANDA Pathway: How Generics Get Approved

Generic manufacturers don’t run full clinical trials. Instead, they file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). The FDA checks two things:

- Pharmaceutical equivalence: Same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, route of administration, and meets the same quality standards.

- Bioequivalence: Proven through the PK studies described above.

If both are met, the FDA approves the generic. The process usually takes 10-12 months. About 65% of first-time ANDAs get approved on the first try. The rest get deficiency letters-often because the dissolution profile didn’t match, or the bioequivalence data had gaps.

Since 2021, the FDA requires companies to submit all bioequivalence studies they ran-even the ones that failed. This isn’t just bureaucracy. It’s transparency. If a company ran five studies and only one worked, the FDA now sees all five. That helps catch hidden problems and prevents cherry-picking data.

Why This Matters for You

Over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. They save the healthcare system an estimated $1.7 trillion over the last decade. But trust doesn’t come from price tags. It comes from science.

The FDA’s bioequivalence standards aren’t perfect, but they’re backed by decades of data. Studies show generic drugs perform just as well as brand names in real-world use-for blood pressure, cholesterol, depression, diabetes, and more. The myth that generics are “weaker” or “less reliable” isn’t supported by evidence.

Still, some patients report feeling different after switching. That’s usually due to changes in inactive ingredients-fillers, dyes, or coatings-that affect how the pill tastes or how fast it dissolves. Rarely, these differences cause minor side effects. But they don’t mean the drug isn’t bioequivalent. If you notice a change, talk to your doctor. Don’t assume the generic failed the test.

What’s Next for Bioequivalence

The FDA is working on new ways to prove equivalence for complex products-like injectables, nasal sprays, and transdermal patches. These are harder to test because they don’t behave like simple pills. New methods using computer modeling and advanced lab tools are being developed to reduce the need for human trials.

By 2025, the FDA expects to approve 20% more complex generics than in 2020. That means more affordable options for conditions like cystic fibrosis, multiple sclerosis, and cancer. But the core rule won’t change: if it’s supposed to enter your bloodstream, it must do so in the same way as the original.

For patients, this means more choices. For the system, it means lower costs. For science, it means a system that works-without cutting corners.

Do generic drugs have the same active ingredient as brand-name drugs?

Yes. By law, generics must contain the same active ingredient, in the same strength and dosage form, as the brand-name drug. The difference lies in inactive ingredients like fillers or coatings, which don’t affect how the drug works-but can affect how it dissolves in your body.

Why do some people say generics don’t work as well?

Some patients notice differences in side effects or how quickly they feel relief after switching. This is usually due to variations in inactive ingredients, not the active drug. The FDA’s bioequivalence standards ensure the active ingredient behaves the same way. If you experience a problem, talk to your doctor-don’t assume the generic failed testing.

Is the 80-125% range too loose? Could a generic be 45% weaker?

No. The 80-125% range applies to how your body absorbs the drug (Cmax and AUC), not the amount of active ingredient in the pill. The pill must contain exactly the same amount of active drug. The range ensures the absorption rate and total exposure are within a safe, clinically insignificant range-not a 45% difference in dosage.

How does the FDA ensure consistency across batches of generic drugs?

Manufacturers must follow strict quality control rules under Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). The FDA inspects their facilities regularly. Each batch must meet the same dissolution and bioavailability profile as the one tested in the original bioequivalence study. If a batch fails, it’s rejected.

Are all generic drugs required to be bioequivalent?

Yes. Every generic drug approved by the FDA must prove bioequivalence unless it’s a product that acts locally (like a topical cream or eye drop), where in vitro testing is sufficient. There are no exceptions for systemic drugs-those that enter the bloodstream.

Okay but like… I switched my blood pressure med to generic last year and I swear I felt weird for a week. Not sick, just… off. Turns out the new pill had a different coating and it gave me heartburn. Not the drug’s fault, just the filler. My doctor laughed and said, ‘That’s why we call them inactive ingredients.’ Funny how something ‘inactive’ can still mess with your gut.

Still, I trust the system. If the FDA says it’s good, I’m good.

80-125% feels like a loophole… but it’s not. It’s math. It’s science. It’s the difference between ‘close enough’ and ‘actually safe.’

Think of it like baking. If your cake recipe says 1 cup sugar, you can’t just dump in 0.8 cups and call it ‘equivalent.’ But if you use a different brand of sugar that dissolves slower, and the cake still rises the same? You’re fine.

The FDA isn’t letting generics be weaker-they’re letting them be *different* in delivery, not effect. That’s genius. 🧠💊

America invented the pill. America regulates it. And now some foreign company wants to slap their name on it and sell it for 10 bucks? Nah. I don’t care if the math checks out. I want the brand. I want the name I know. I want the American-made one. This ‘bioequivalence’ nonsense is just globalism in a lab coat.

My grandpa took the real thing. I’ll take the real thing too.

This is one of the most important public health stories you’ll never hear on the news. Generics aren’t just cheaper-they’re *just as good*, and the science behind them is incredibly rigorous.

For decades, patients have been told to fear generics. That fear is rooted in misinformation, not data. The FDA’s 80-125% range? It’s not arbitrary. It’s based on decades of clinical outcomes, statistical modeling, and real-world patient results.

Every time someone chooses a generic, they’re not just saving money-they’re helping the entire healthcare system breathe. And that’s something to celebrate.

Let’s stop calling them ‘cheap alternatives’ and start calling them what they are: scientifically validated, life-saving medicines.

Thank you to every scientist, regulator, and pharmacist who makes this possible. You’re doing vital work.

They say generics are fine but I’ve seen people crash after switching. I know a guy who went from 100mg to 93mg and he ended up in the ER. The FDA doesn’t care about real people. They care about numbers on a spreadsheet. 80-125%? That’s a death sentence waiting to happen. And they call it science. It’s not science. It’s corporate greed wrapped in a lab coat.

Stop lying to us.

They don’t test on old people. They don’t test on people with kidney disease. They test on 24 healthy college kids who probably don’t even eat real food. That’s not medicine. That’s a casino.

Interesting that they require all studies to be submitted now-even the failed ones. That’s actually kind of a big deal. Most companies would bury those. Transparency is rare in pharma.

Still… I wonder how many ‘failed’ studies were just tweaked until they passed. Like, what if they changed the fasting window or the time of day the pill was taken? That’s not cheating… but is it honest?

Just saying. The system’s good. But humans run it.

India makes 20% of the world’s generics. We don’t cut corners. We make them right. I work in pharma. The labs here are clean, the data is tracked, the tests are strict. The FDA doesn’t approve just anyone. If your generic gets approved, you earned it.

Stop acting like generics are ‘made in a basement.’ They’re made in factories with more controls than your iPhone factory.

And yes, we have the same standards. Maybe even stricter sometimes.

my doc switched me to generic lisinopril and i swear i felt like a new person. no more dizziness. no more headaches. turned out my brand name had this weird dye that was messing with my nervous system. generic didn’t. so yeah, sometimes the ‘inactive’ stuff is the problem.

also-i once got a generic that tasted like metal. it was gross. but it worked. so i just swallowed it fast and moved on. science is weird but it’s real.