When a patient can’t swallow, giving them medication through a feeding tube seems simple. But it’s not. One wrong move-crushing a pill that shouldn’t be crushed, skipping a flush, or mixing meds with formula-can lead to a blocked tube, a failed treatment, or even poisoning. In fact, medication errors during enteral feeding cause 15-20% of all adverse events linked to feeding tubes, according to the Veterans Affairs safety reports from 2023. This isn’t a rare mistake. It happens daily in hospitals, nursing homes, and home care settings. And the stakes? Life or death.

Why Tube Compatibility Matters More Than You Think

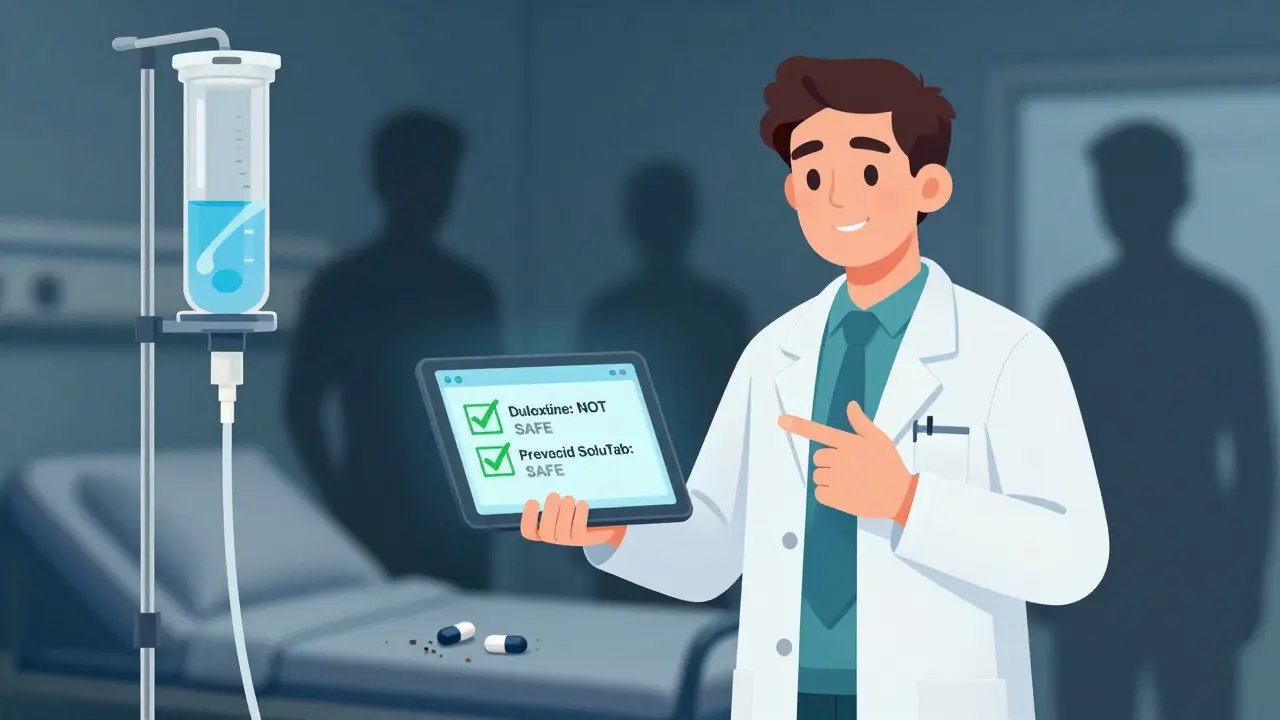

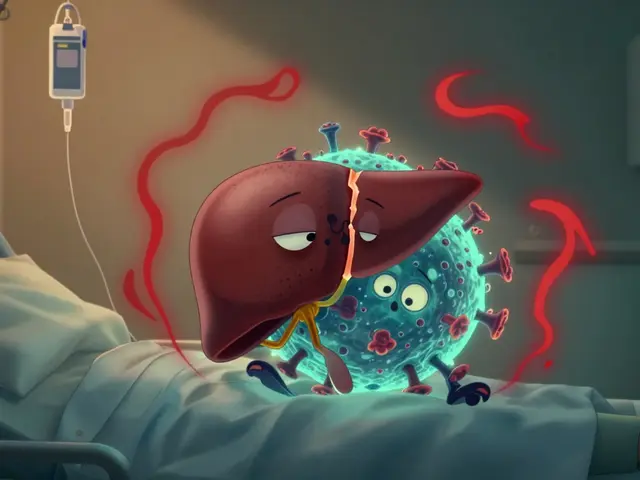

Not all pills are made to go through a feeding tube. Some are designed to dissolve slowly, others to avoid stomach acid, and some contain tiny pellets or coatings that will clog a tube the moment you crush them. The internal diameter of these tubes ranges from 5 to 16 French (about 1.7 to 5.3 mm). Smaller tubes-like those under 8 French-are especially vulnerable. A single crushed extended-release tablet can turn into a stubborn plug that takes hours to clear, if it clears at all. The NIH studied 323 oral medications and found that only 78% of immediate-release tablets dissolved properly in water within five minutes. For extended-release versions? That number dropped to 32%. That means more than two out of every five pills you crush won’t pass through safely. And some? They’re outright dangerous. Medications like mycophenolate (Cellcept®), valganciclovir (Valcyte®), and finasteride (Proscar®) are absolute no-go zones for crushing. Crushing these releases toxic levels of active ingredients, risking serious harm. Even something as common as psyllium (Metamucil®)-a bulk-forming laxative-can cause immediate, catastrophic blockage. It swells up in the tube like a sponge. One dose, and you’re looking at a tube replacement. Enteric-coated pills are another trap. These have a shell that keeps the drug from dissolving in the stomach. If you crush them, the medication releases too early and can be destroyed by stomach acid or cause irritation. Duloxetine capsules, for example, contain enteric-coated pellets. The NIH explicitly warns: “Not for feeding tube use.”The Flushing Rule: 15 mL Is the Minimum

Flushing isn’t optional. It’s non-negotiable. And it’s not just about clearing the tube after the med. You flush before, between, and after every single medication. The Cleveland Clinic’s guideline is clear: use at least 15 mL of water for every 10 mL of medication. That means if you give 20 mL of liquid medication, you need 30 mL of water flushes total. For tablets, even if they’re dissolved, you still need a full 15 mL before and after. Why? Because even a tiny bit of residue left behind builds up over time. One nurse in Manchester told me she saw a G-tube clog after just three days because the staff were only using 5 mL flushes. They thought it was enough. It wasn’t. And don’t use juice, soda, or feed to flush. Water is the only safe option. Other liquids can react with meds or cause precipitation. Even sterile water is better than tap water if you’re unsure of your water quality. And never skip the flush between meds. Two drugs mixing inside the tube can form a chemical sludge. That’s how you get a blocked tube and a patient without their antibiotics.What You Can and Can’t Crush

Let’s cut through the confusion. Here’s what works and what doesn’t:- Safe to crush: Immediate-release tablets without coatings, plain capsules opened and mixed with water (if contents are soluble), liquid suspensions.

- Never crush: Extended-release tablets (like diltiazem ER, metoprolol succinate), enteric-coated pills (omeprazole capsules), film-coated tablets (some SSRIs), capsules with pellets (duloxetine, venlafaxine XR), and any medication labeled “do not crush.”

- Special case: Prevacid® SoluTabs are designed to dissolve evenly in water and are safe for tubes. But regular Prevacid capsules? Not okay.

Tube Placement Check: Don’t Skip It

Before you give a single drop of medication, confirm the tube is in the right place. You can’t assume it is. Tubes can migrate. A nasogastric tube that’s slipped into the lungs? Giving meds there can cause pneumonia or death. Use pH testing. Aspirate gastric fluid. If the pH is less than 5.5, it’s likely in the stomach. If you’re unsure-or if the patient is on acid-suppressing meds-get an X-ray. Document it. Every time. RCH Nursing guidelines say it’s an administration error if you don’t. And it’s not just paperwork. It’s safety.Why Withholding Feedings Usually Isn’t Necessary

For years, nurses were told to stop feeding for 30 to 60 minutes before and after meds. That’s outdated. The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) reviewed decades of data and found that, except for levodopa, there’s no clinical reason to pause feeding for most medications. Levodopa competes with amino acids in the feed for absorption. That’s the only case where timing matters. For everything else-antibiotics, blood pressure meds, antiseizure drugs-you can give them with the feed. Just flush properly. Stopping feedings unnecessarily leads to calorie deficits, longer hospital stays, and frustrated families.What Happens When You Get It Wrong

A 72-year-old man in a care home was given crushed diltiazem ER tablets through his G-tube. The extended-release coating was destroyed. The drug flooded his system all at once. His heart rate dropped dangerously low. He was rushed to the hospital. His family was told he might not recover. The error? The nurse didn’t know the difference between immediate-release and extended-release. The tube wasn’t flushed between meds. The feeding continued without pause. That’s not rare. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) says medication errors in enteral feeding are among the top 10 preventable harms in healthcare. And the cost? Not just to patients. A blocked tube adds $1,200 to $3,500 in hospital costs per incident. That’s $3.8 billion industry-wide, with 12% of those costs tied to medication errors.

How to Get It Right

Here’s your checklist:- Verify tube placement with pH test or X-ray. Document it.

- Check compatibility with a pharmacist or trusted database (like the NIH’s 323-drug list).

- Use only immediate-release or tube-safe formulations. Never crush extended-release, enteric-coated, or pellet-filled meds.

- Flush with 15 mL water before the first med.

- Flush with 15 mL water between each medication.

- Flush with 15 mL water after the last med.

- Never mix meds with formula. Always give meds separately.

- Document everything: What was given, how it was prepared, flush volume, tube check result.

The Future Is Safer-If We Act Now

The FDA’s 2021 draft guidance is pushing drug makers to test their products for tube compatibility. Some companies are starting to label their meds as “suitable for enteral administration.” That’s a big step. But until then, the burden is on us. Hospitals that use electronic alerts in their systems-like the VA’s CPRS CROC tool-have seen dramatic drops in errors. Pharmacists are now routinely consulted before any tube med is ordered. That’s the gold standard. For home caregivers, the challenge is even greater. The Oley Foundation reports that 40% of home enteral complications come from medication mistakes. No pharmacist nearby. No nurse on call. Just a family member trying to do the right thing. The message is simple: Don’t guess. Don’t rush. Don’t assume. Know before you tube.Can I crush any pill if I dissolve it in water?

No. Crushing is only safe for immediate-release tablets without special coatings. Extended-release, enteric-coated, and pellet-filled medications must never be crushed-even if you dissolve them. Crushing destroys their design, which can lead to overdose, toxicity, or reduced effectiveness. Always check a reliable compatibility database or ask a pharmacist before crushing any pill.

How much water should I use to flush a feeding tube?

Use at least 15 mL of water before giving the first medication, 15 mL between each medication, and 15 mL after the last one. For every 10 mL of medication given, use at least 15 mL of flush water. Never use juice, formula, or other liquids to flush-only sterile or clean water. Inadequate flushing is the leading cause of tube blockages.

Is it safe to mix medications with enteral formula?

No. Mixing medications directly into the feeding formula can cause chemical reactions, precipitation, or reduced drug absorption. It can also clog the tube. Always give medications separately, with proper flushing between each one. Only mix meds into formula if there’s published, peer-reviewed evidence proving compatibility-and even then, it’s rarely recommended.

Which medications are absolutely unsafe for feeding tubes?

Never crush or administer through a tube: mycophenolate (Cellcept®), valganciclovir (Valcyte®), finasteride (Proscar®), psyllium (Metamucil®), extended-release tablets (like diltiazem ER or metoprolol succinate), and enteric-coated capsules (like duloxetine or omeprazole). These can cause toxicity, tube blockage, or loss of drug effect. Always verify each medication using a trusted source like the NIH’s enteral compatibility database.

Do I need to stop feeding before giving meds?

Only for levodopa. For nearly all other medications, you can give them with the feeding. Stopping feedings unnecessarily can lead to malnutrition and longer recovery times. The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) found no clinical benefit to withholding feedings for other drugs. Just make sure to flush properly before and after each med.

What should I do if the tube gets blocked?

Don’t force water or use cola or enzymes unless instructed. First, try flushing with warm water using a 60 mL syringe and gentle back-and-forth motion. If that doesn’t work, contact a nurse or pharmacist immediately. Never use sharp objects to clear the tube. Most blockages can be resolved with proper flushing techniques if caught early. Prevention is always better than cleanup.

Who should check if a medication is safe for a feeding tube?

A pharmacist is the best person to verify medication compatibility. They have access to databases like the NIH’s 323-drug list and can identify safe alternatives (e.g., switching from a crushed extended-release tablet to a liquid form). Nurses and caregivers should never make this decision alone. Always consult pharmacy services before administering any medication through a tube.

Can I use tap water to flush the tube?

Clean tap water is generally acceptable for flushing in home settings if it’s safe to drink. In hospitals or for immunocompromised patients, sterile water is preferred. Avoid using bottled water with added minerals or electrolytes-these can cause precipitation. The key is consistency: use the same water type each time to reduce risk.

I've seen nurses flush with 5mL because they're 'in a rush.' Then the tube clogs, the patient goes 12 hours without meds, and suddenly it's 'Whoops, my bad.' This isn't nursing. This is Russian roulette with a feeding tube.

One hospital in Cork had a 60% drop in blockages after they made flush logs mandatory. Simple. No excuses.

The pharmacokinetic implications of crushing extended-release formulations via enteral routes are non-trivial. The loss of controlled-release matrices results in Cmax spikes that can exceed therapeutic thresholds by 300-500%, particularly with calcium channel blockers like diltiazem ER. Moreover, enteric-coated pellets bypass gastric pH regulation, leading to premature degradation or mucosal irritation. The NIH dataset you referenced is robust, but institutional pharmacy protocols-particularly those incorporating electronic decision support-are the true linchpin for risk mitigation.

We treat these tubes like they're just a pipe and the meds are coffee. But it's not a coffee maker. It's a lifeline. And we're the ones who keep it from clogging. The real tragedy isn't the blocked tube-it's that we act like this is common sense when it's clearly not. Someone had to write this whole guide because too many people assumed they already knew.

Maybe if we stopped treating caregivers like disposable robots, we'd stop having these disasters.

The administration of pharmaceutical agents via enteral feeding tubes constitutes a high-risk clinical procedure that demands strict adherence to evidence-based protocols. Failure to comply with standardized flushing regimens, failure to verify tube placement via pH analysis, and failure to consult pharmacological compatibility databases represent systemic deviations from accepted standards of care. Such deviations are not merely procedural oversights-they are breaches of the duty of non-maleficence.

I used to think flushing was just a suggestion until my grandma got a tube and we gave her crushed pills with no water between. Three days later the tube was full of gunk and we had to rush her to the ER. The nurse looked at us like we’d just set fire to the hospital. I’ve never felt so stupid in my life. 15mL. BEFORE. BETWEEN. AFTER. I write it on my hand now. Don’t be like me.

You say 'don't guess'-but you also say 'pharmacists are the only ones trained.' That’s not a solution. That’s outsourcing responsibility. If a nurse can’t verify compatibility, they shouldn’t be administering meds. Period. This isn’t a ‘we’re all just trying our best’ situation. It’s a competency issue. And if your hospital doesn’t train nurses to interpret compatibility databases, then your hospital is failing its patients. No excuses.

I work in home care. The families are terrified. They don’t have pharmacists on speed dial. They don’t have time to check databases. They’re doing this while working full-time, caring for kids, and grieving. We need simple, printed cheat sheets. Color-coded. Laminated. Posted on the fridge. Not every nurse has time to be a pharmacist. But we can make sure the people doing the work have the tools to get it right.

It’s not about blame. It’s about building bridges.

I’m from Kenya and we don’t have pharmacy services in half the rural clinics. We crush pills because it’s the only way the patient gets meds. I get your guidelines. I really do. But what do you do when your only option is to risk a blockage or risk the patient dying of infection because they missed their antibiotics? The real problem isn’t the flushing-it’s that we’re asking people in resource-poor settings to follow guidelines written for hospitals in Boston. We need solutions that fit reality, not just theory.