When a blockbuster drug’s patent is about to expire, you might think the market opens up to cheaper generics right away. But that’s not how it usually works. Instead, the brand-name company often rolls out a new version - a slightly different pill, a new capsule, a changed dose - and files a new patent. This trick, called evergreening, keeps generics off the market for years longer than they should be. And it’s not an accident. It’s a calculated strategy used by nearly every major pharmaceutical company to protect billions in revenue.

How Evergreening Works - And Why It’s Legal

Evergreening isn’t about inventing new medicine. It’s about tweaking old ones. A company might change the time-release mechanism of a drug, combine it with another ingredient, or switch from a tablet to a liquid. These aren’t breakthroughs. They’re minor tweaks. But under U.S. patent law, even small changes can qualify for a new patent - if the company can show the modification was "non-obvious" and had some clinical benefit.

The system was designed to balance innovation with access. The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act gave drugmakers 20 years of patent protection from the date of filing, plus up to five extra years for clinical trials. It also created a fast-track for generics to enter the market once patents expired. But loopholes were built in. Companies learned to exploit them. Instead of waiting for the original patent to expire, they start filing new ones five to seven years before that date. Some drugs end up with dozens of patents stacked on top of each other.

Take Humira, the autoimmune drug made by AbbVie. Between 2002 and 2023, AbbVie filed 247 patent applications related to Humira. Over 100 were granted. That’s not innovation - that’s a legal shield. These patents covered everything from dosing schedules to manufacturing methods. The result? Generic versions were blocked until 2023 - 21 years after the original approval. By then, Humira had generated over $200 billion in sales. Each day, it made about $40 million in profit. That’s the power of evergreening.

Common Tactics Used to Extend Monopolies

There are several standard moves in the evergreening playbook:

- Product hopping: When a company replaces its original drug with a new version - often with a minor change - and stops making the old one. Patients and doctors are pushed to switch, even if the new version offers no real benefit. AstraZeneca did this with Prilosec and Nexium. Nexium was essentially the same acid-reducing drug, just in a different form. The company marketed it as "the purple pill" and convinced doctors it was better. The result? Generics for Prilosec flooded the market, but Nexium stayed protected for years longer.

- Patent thickets: Instead of one patent, companies file dozens. This creates a legal maze. Generic manufacturers can’t risk entering the market unless they challenge every single patent - a process that costs millions and takes years. Even if they win one, another patent pops up.

- Authorized generics: Sometimes, the brand company launches its own generic version right before the patent expires. It sells at a lower price, but only through its own channels. This confuses the market and keeps independent generics from gaining traction.

- Pediatric exclusivity: If a company tests a drug on children - even if the drug isn’t meant for kids - they get six extra months of protection. This is allowed under law, but it’s often used as a loophole. The clinical trials are minimal, but the payoff is huge.

- OTC-switching: A company may switch a drug from prescription to over-the-counter. This doesn’t extend the patent, but it lets them keep selling the brand version at a high price while generics are still blocked from the prescription market.

These tactics aren’t rare. A 2019 Harvard study found that 78% of new patents on prescription drugs were for existing drugs, not new ones. That means most patent activity isn’t about innovation - it’s about delay.

The Cost to Patients and the Health System

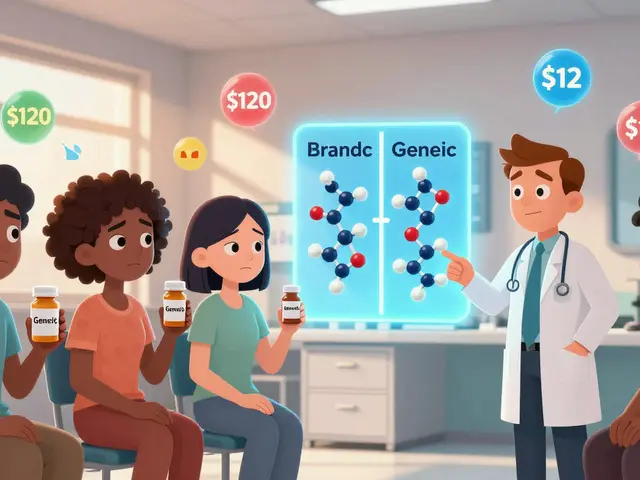

When generics enter the market, prices drop - fast. Studies show drug prices fall by 80% to 85% within the first year after generic approval. That’s life-changing for people who need daily medication for diabetes, high blood pressure, or autoimmune diseases.

But when evergreening blocks generics, patients pay more. For example, a 30-day supply of the original version of Nexium cost over $200 before generics arrived. After generics hit, it dropped to under $20. That’s a 90% drop. But because AstraZeneca used evergreening to delay that drop by years, millions of patients paid hundreds of dollars a month longer than they should have.

The financial burden falls hardest on those without good insurance. In the U.S., one in four adults skip doses because they can’t afford their meds. Evergreening plays a role in that. It’s not just about money - it’s about access. If a patient can’t afford their drug, they might skip doses, end up in the ER, or develop complications that cost the system far more in the long run.

Why Companies Keep Doing It

It’s simple: the financial reward outweighs the risk. Developing a brand-new drug costs about $2.6 billion and takes over a decade. Evergreening? It costs a fraction of that. A new formulation might take two years and $50 million to develop. The payoff? Extra years of monopoly pricing, often adding billions to revenue.

Companies have entire teams dedicated to this. Lifecycle management departments work years in advance, studying every possible tweak to a drug. They hire patent lawyers who specialize in pharmaceutical law. They run small clinical trials just to meet the legal requirement for a new exclusivity period. It’s a business model built on timing, legal loopholes, and regulatory inertia.

And it works. Until it doesn’t. Some courts have started pushing back. In 2022, the Federal Trade Commission sued AbbVie over Humira’s patent strategy, calling it an illegal monopoly. The case is still ongoing. In Europe, regulators now require proof of "significant clinical benefit" before granting extra exclusivity. That’s a step forward. But in the U.S., the system still favors brand companies.

What’s Changing - And What’s Not

The tide is slowly turning. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for the most expensive drugs. That directly cuts into the profit motive for evergreening. If the government can cap the price of a drug, there’s less incentive to stretch out a patent for years.

Meanwhile, the World Health Organization has called evergreening a barrier to global health equity. In low- and middle-income countries, where people pay out of pocket, evergreened drugs are often completely unaffordable. Generic versions could save lives - but they’re locked out by patents filed in the U.S. and Europe.

Some companies are adapting. Instead of tweaking pills, they’re moving to biologics - complex, protein-based drugs that are harder to copy. These don’t have simple generic versions; they have "biosimilars," which take longer and cost more to develop. That’s the next frontier for evergreening.

But here’s the truth: we don’t need more patents. We need better rules. The patent system was never meant to be a tool for extending monopolies on old drugs. It was meant to reward real innovation - not minor changes that don’t help patients.

What Can Be Done?

There are three clear paths forward:

- Stricter patent standards: The U.S. Patent Office should require proof of real therapeutic improvement - not just a new capsule or a different dose - before granting new patents on existing drugs.

- Limiting exclusivity stacking: No drug should get more than one extra exclusivity period unless it’s truly new. Pediatric exclusivity and new formulation protections should be capped.

- Fast-tracking generics: The FDA should be given more authority to approve generics even when patents are still active - if the patent is clearly weak or abusive.

Some countries are already doing this. India and Brazil have strict rules against evergreening. Their generic drug industries are strong, and drug prices are far lower. Patients there get access to life-saving medicines without waiting for a patent to expire.

It’s not about killing innovation. It’s about stopping the abuse. The best drugs are still being invented. But most new patents aren’t for new drugs. They’re for old ones - with tiny changes. That’s not progress. That’s profit-driven delay.

What Patients Can Do

If you’re on a brand-name drug that’s about to lose its patent, ask your doctor or pharmacist: "Is there a generic version coming?" If the answer is no - and the drug has been on the market for more than 10 years - it’s worth digging deeper. Sometimes, the brand company is using evergreening to block generics. You can also check the FDA’s Orange Book, which lists all patents on prescription drugs. If you see a long list of patents filed in the last few years, it’s likely evergreening at work.

Advocacy matters too. Contact your representatives. Ask them to support patent reform. The system isn’t broken - it’s working exactly as designed. But it’s designed to protect profits, not patients.

What is evergreening in the pharmaceutical industry?

Evergreening is when pharmaceutical companies file new patents for minor changes to existing drugs - like a new dosage form, a combination with another drug, or a different release mechanism - to delay generic competition. This extends their monopoly beyond the original 20-year patent term, keeping prices high and generics off the market.

Is evergreening legal?

Yes, in many cases, it’s legal under current U.S. patent law. As long as a company can show that a modification is "non-obvious" and supported by new clinical data, even minor changes can qualify for a new patent. But many experts and regulators consider it abusive, especially when the changes offer no real benefit to patients.

How does evergreening affect drug prices?

Evergreening keeps prices high by blocking generic competition. Once generics enter the market, prices typically drop by 80-85%. But when evergreening delays that entry for years - sometimes over a decade - patients pay hundreds or thousands more per year than they should.

What’s the difference between evergreening and real innovation?

Real innovation means discovering a new molecular compound that treats a disease in a new way. Evergreening means tweaking an existing drug - changing its shape, dose, or delivery method - without improving its effectiveness. The cost of evergreening is a fraction of developing a new drug, but the profits are nearly the same.

Which drugs are most affected by evergreening?

Blockbuster drugs with high sales volumes are the main targets. Examples include Humira (for autoimmune diseases), Nexium (for acid reflux), and Prilosec (also for acid reflux). AstraZeneca and AbbVie have been among the most aggressive users of evergreening strategies, extending patent protection for these drugs by decades.

Are there any efforts to stop evergreening?

Yes. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission sued AbbVie over Humira’s patent strategy in 2022. The Inflation Reduction Act now lets Medicare negotiate drug prices, reducing the financial incentive for evergreening. The European Medicines Agency also requires proof of real clinical benefit before granting extra exclusivity. But enforcement remains inconsistent, and the practice continues.

Evergreening isn’t a glitch in the system - it’s a feature. And until the rules change, patients will keep paying the price.

Did you know the FDA has a secret backdoor deal with Big Pharma? They don’t tell you this, but every time a patent expires, the agency gets a kickback from the brand company to delay generics - just enough to keep the cash flowing. I’ve got insider docs from a whistleblower at the NIH. They call it ‘Project Evergreen.’ You think this is about health? Nah. It’s about control. The same people who make your insulin also own the servers that track your blood sugar apps. They’re not just selling drugs - they’re selling your life data. And you’re paying for it twice.

It is not merely a matter of legal loopholes or corporate greed; it is a systemic failure of epistemic humility in regulatory architecture. The patent regime, originally conceived to incentivize novelty, has been perverted into a mechanism of temporal monopolization, wherein incrementalism masquerades as innovation. The moral economy of pharmaceuticals must be reoriented from shareholder value to human flourishing. The Indian and Brazilian models, grounded in public health imperatives rather than intellectual property absolutism, offer not merely alternatives but moral precedents. We must ask: is a patent a right, or is it a social contract?

The structural inefficiencies in the Hatch-Waxman framework are non-trivial. The 5-year exclusivity extension coupled with the lack of substantive clinical threshold for new chemical entities creates negative externalities in drug pricing elasticity. The FTC’s litigation against AbbVie is procedurally sound but substantively inadequate - they’re still operating within the same regulatory ontology that enabled the problem. What’s needed is a redefinition of ‘non-obviousness’ under 35 U.S.C. § 103 to include therapeutic utility metrics, not just pharmacokinetic variance. Until then, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

LMAO so the real villain is… a pill? 🤡

Brooo this is why Nigeria can’t get cheap meds! These American pharma bros sitting in their penthouses with Humira money, while my cousin in Lagos is taking half a tablet because the real one costs 3 months’ salary. This ain’t capitalism - this is medical colonialism. They patent the cure, then charge us for the right to breathe. I’m so mad I could scream into a pillow for 3 hours straight 😭

Oh sweetie, you think this is new? 😏 I’ve been working in Indian generics for 12 years. We’ve been making Humira copies since 2015 - just not in the US. The FDA doesn’t approve them because AbbVie sues anyone who tries. Meanwhile, in Bangladesh, a 30-day supply costs $12. In the US? $18,000. The only thing ‘innovative’ here is how perfectly they’ve engineered the system to make you feel guilty for wanting to live. Want to fix it? Don’t ask your rep. Buy Indian generics. Then tell everyone how you did it.

i just read this and now i’m crying because my dad’s blood pressure med is $500 a month and he skips doses to make it last… like why is this even a thing?? i thought patents were for inventing stuff?? not just changing the color of the pill?? 🤦♀️

Okay, let’s get real - this isn’t just about drugs, it’s about power. And the power is in the hands of people who don’t care if you live or die as long as your insurance card swipes. But here’s the good news: you’re not powerless. You can demand reform. You can support organizations fighting this. You can ask your doctor for generics - even if they’re not on the shelf yet, they exist. And you can vote. Not just for the big names - for the local reps who actually vote on patent law. This isn’t a conspiracy. It’s a business model. And business models can be changed. You just have to stop being quiet.