Scar Risk Calculator

How likely are you to develop a noticeable scar?

Enter details about your abrasion to calculate your risk level and receive personalized prevention advice.

When your skin suffers a scrape, that’s an Abrasions shallow injuries that damage the outer skin layers, usually the epidermis, without breaking deeper tissue. Most people think a scrape is just a minor nuisance, but the way your body repairs it can leave lasting marks - Scar tissue fibrous tissue that replaces normal skin after injury, often differing in color and texture. Understanding the link between these two helps you take steps that keep a scar from turning into a permanent reminder.

Key Takeaways

- Abrasions damage the Epidermis the outermost skin layer that protects against infection and sometimes reach the Dermis the deeper layer containing collagen and blood vessels.

- The body’s Wound healing process involves inflammation, tissue formation, and remodeling determines whether a scar will be flat, raised, or pigmented.

- Factors like depth of injury, infection, genetics, and sun exposure heavily influence scar severity.

- Prompt, clean first‑aid and targeted scar‑reduction treatments can cut the risk of permanent scarring by up to 50%.

- Seek professional care if the wound is large, gaping, or shows signs of infection; early intervention prevents worse outcomes.

Understanding Abrasions

Think of an abrasion as a road‑scratch on your skin. It usually occurs when friction removes the Epidermis the protective outer skin layer while leaving the deeper layers mostly intact. Common causes include falls on concrete, sports injuries, or even a rough pet’s nail.

Even though abrasions are classified as “minor,” they create an open portal for bacteria. If you ignore cleaning the wound, inflammation can become prolonged, setting the stage for excess collagen deposition - the main culprit behind thick, raised scars.

How Scars Form

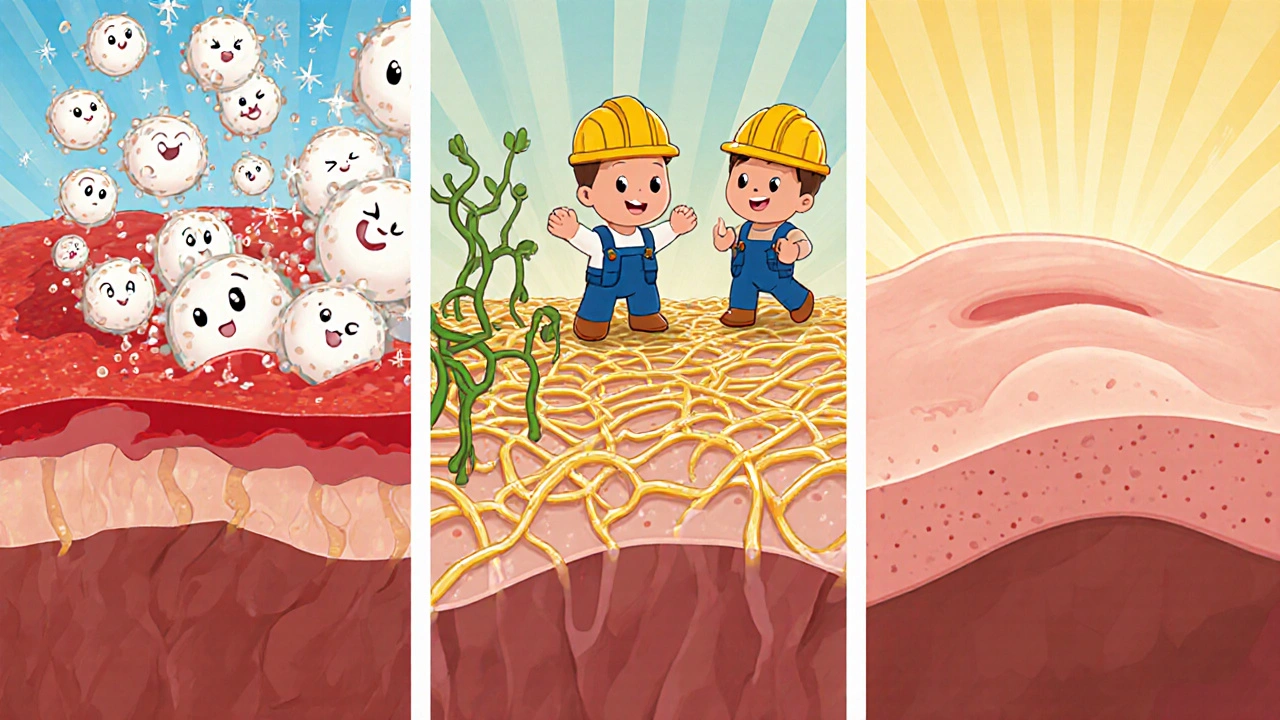

After an abrasion, your body launches a three‑phase response:

- Inflammation (Days 0‑3): Blood vessels constrict then dilate, flooding the area with white blood cells. This clears debris but also releases cytokines that signal fibroblasts to start working.

- Proliferation (Days 3‑14): Fibroblasts, the “construction crew,” lay down Collagen a protein that gives skin strength and structure. New blood vessels form, and a thin layer of new epidermis covers the wound.

- Remodeling (Weeks 2‑12+): Collagen fibers reorganize, aligning with tension lines. If too much collagen remains, the scar thickens; if too little, the scar may be depressed.

People who develop Keloid overgrown, rubbery scar that extends beyond the original injury or Hypertrophic scar raised scar confined to the wound margins often have a genetic predisposition that pushes fibroblasts into overdrive.

Factors Influencing Scar Severity

| Factor | Impact on Scarring | Practical Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Depth of abrasion | Deeper wounds reach the dermis, increasing collagen response. | Keep the wound moist and protect with sterile dressings. |

| Infection | Prolonged inflammation leads to excess scar tissue. | Clean with mild antiseptic; apply antibiotic ointment. |

| Genetics | Some people naturally overproduce collagen. | Consider silicone gel sheets or pressure therapy early. |

| Sun exposure | UV rays boost melanin, causing darkened scars. | Use SPF 30+ sunscreen for at least 6 months. |

| Age | Older skin regenerates slower, often yielding thicker scars. | Support healing with vitamin C serum and proper nutrition. |

Effective First‑Aid for Abrasions

The moment you notice a scrape, follow these steps:

- Rinse gently: Use lukewarm water and mild soap to remove dirt. Avoid harsh scrubbing - you don’t want to widen the wound.

- Disinfect: Apply a thin layer of over‑the‑counter antiseptic (e.g., povidone‑iodine). This kills surface bacteria without irritating the tissue.

- Moisturize: A petroleum‑based ointment creates a moist environment, which research shows speeds re‑epithelialization by 30%.

- Cover: Use a non‑stick sterile dressing. Change it daily or when it becomes wet.

- Protect from sun: If the wound is on an exposed area, apply a broad‑spectrum sunscreen once the dressing is removed.

These steps reduce the inflammatory phase’s length, giving fibroblasts a tighter schedule and less chance of over‑producing collagen.

Treatment Options to Reduce Scars

Even with perfect first‑aid, some scar formation is inevitable. Here are evidence‑based options you can start once the wound has closed (usually 7‑10 days):

- Silicone gel sheets: Clinically proven to flatten raised scars by maintaining hydration and applying gentle pressure.

- Massage therapy: Massaging scar tissue with a moisturizer for 5‑10 minutes daily helps re‑align collagen fibers.

- Vitamin C serums: Topical antioxidants boost collagen remodeling and lighten hyperpigmented scars.

- Laser resurfacing: For stubborn scars, fractional lasers break down excess collagen and stimulate fresh skin growth. Requires a dermatologist.

- Pressure garments: Often used for large burns or keloids, they compress the scar, limiting blood flow and collagen buildup.

Pick the method that matches your scar type and lifestyle. Most people see noticeable improvement within 8‑12 weeks of consistent treatment.

When to Seek Professional Care

While many abrasions heal nicely at home, certain red flags mean you should call a health professional:

- Wound larger than 2 cm, deep, or with a gaping edge.

- Signs of infection: increasing redness, warmth, swelling, pus, or fever.

- Location over a joint where movement could reopen the wound.

- History of abnormal scarring (keloids or hypertrophic scars).

Early debridement, suturing, or prescription‑strength ointments can dramatically lower long‑term scarring risk.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can an abrasion cause a keloid?

Yes, if the abrasion penetrates into the dermis and the person has a genetic tendency, the fibroblasts may overproduce collagen, leading to a keloid. Early scar‑modulating treatment reduces this risk.

How long does it take for a scar to mature?

Most scars reach their final appearance between 6 months and 2 years. The first few weeks are critical for controlling inflammation and hydration.

Is sunscreen really necessary for a fresh scar?

Absolutely. UV radiation can darken a new scar up to 30 % more than surrounding skin, making it more noticeable. Apply SPF 30+ at least twice daily until the scar is fully matured.

Can natural remedies like honey help?

Medical‑grade honey has antibacterial properties and can keep a wound moist, which aids healing. However, evidence for reducing scar size is limited compared with silicone or pressure therapy.

Should I avoid picking at a scab?

Never. Picking disrupts the remodeling phase, can re‑introduce bacteria, and often leads to a thicker, more pigmented scar.

By understanding how abrasions turn into scar tissue, you can intervene early, choose the right after‑care, and keep your skin looking as smooth as possible. Remember, the best scar‑prevention strategy starts with clean, moist, and protected healing.

When an abrasion is left to dry out, the epidermal barrier breaks down faster than you realize, and the subsequent inflammatory surge can set the stage for a hypertrophic scar.

First, rinse with lukewarm water – hot water will denature proteins and cold water stalls perfusion.

Apply a thin layer of petroleum‑based ointment to keep the wound moist; this isn’t just comfort, it’s a proven method to accelerate re‑epithelialization.

Cover with a non‑stick sterile dressing and change it at least once daily.

Finally, protect the healing tissue from UV rays with SPF 30+; even a light tan can hyper‑pigment a newborn scar.

Follow these steps and you’ll dramatically reduce the odds of a permanent reminder.

clean it good and dont pick

The wound healing cascade reminds me of a slow river, each phase follows the last with quiet inevitability. Inflammation clears debris but also signals fibroblasts to lay down collagen. The proliferation stage builds new tissue, then remodeling refines the architecture. Trust the process, avoid unnecessary interference, and the scar will be modest.

I've seen countless cases where a simple slip on concrete turned into a painful keloid just because the person ignored proper after‑care. You deserve a scar that fades, so keep the abrasion moist, use silicone sheets once the skin closes, and never let the sun scorch the fresh tissue. Remember, the body is already doing the hard work; our job is to guide it gently. Your commitment to consistent care makes all the difference.

Hey folks, great points already shared! Keeping the wound hydrated is the secret sauce – think of it like giving your skin a mini‑spa. A thin layer of petroleum jelly plus a breathable dressing creates the perfect environment for fibroblasts to work efficiently. Add a dab of vitamin C serum after the scab falls off and you’ll see a brighter, smoother patch. Stick to the routine and you’ll be amazed at how minimal the final mark becomes.

One must appreciate the exquisite choreography of collagen deposition; the dermis orchestrates a symphony of fibroblastic activity that, if unchecked, births an unsightly protrusion. Yet the layperson, armed with mere ointment, seldom grasps this nuance. Moisture retention, modestly achieved through petroleum jelly, is the conductor’s baton that tempers this exuberant performance. Neglect it and you invite chaos-a scar of undue prominence.

From a dermatopathological perspective, the transition from an epidermal abrasion to a clinically evident scar is mediated by a cascade of molecular events that can be segmented into three distinct phases: hemostasis, inflammation, and proliferative remodeling. During hemostasis, platelet aggregation induces fibrin clot formation, establishing a provisional matrix that serves as a scaffold for subsequent cellular infiltration. The inflammatory milieu is characterized by the upregulation of cytokines such as interleukin‑1β, tumor necrosis factor‑α, and chemokine ligand‑2, which orchestrate neutrophil chemotaxis and macrophage activation. Macrophages, in turn, secrete transforming growth factor‑β1 (TGF‑β1), a pivotal growth factor that stimulates fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix synthesis. Fibroblasts deposit type III collagen initially, which is later remodeled into type I collagen through the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs). An imbalance favoring TGF‑β1 over matrix degradation precipitates excessive collagen deposition, clinically manifesting as hypertrophic or keloidal scarring. Genetic polymorphisms in the SMAD signaling pathway have been correlated with heightened fibroblastic responsiveness, thereby augmenting scar severity in predisposed individuals. Moreover, ultraviolet radiation impairs the regulatory feedback loop by upregulating melanocyte‑stimulating hormone, resulting in hyperpigmentation of the nascent scar tissue. Clinical guidelines therefore advocate for early intervention with silicone occlusion therapy, which exerts semi‑permeable pressure and modulates epidermal hydration, thereby attenuating fibroblast activity. Adjunctive modalities such as fractional laser resurfacing disrupt aberrant collagen bundles, inducing controlled dermal remodeling while stimulating neocollagenesis. Topical agents containing ascorbic acid function as co‑factors for prolyl hydroxylase, enhancing the hydroxylation of procollagen and promoting organized fibril assembly. It is imperative to initiate these therapeutic strategies within the first 7–10 days post‑injury to maximize efficacy, as the proliferative phase is most receptive to modulation during this temporal window. In conclusion, a mechanistic understanding of the cytokine‑fibroblast axis, coupled with evidence‑based adjuncts, empowers clinicians to mitigate the trajectory from a simple abrasion to a conspicuous scar. Future research should focus on targeted inhibition of TGF‑β1 signaling pathways to further refine scar prevention protocols. Until such innovations become mainstream, diligent wound care remains the cornerstone of optimal dermatologic outcomes.

The wound cries out for attention, yet we treat it as an afterthought; this neglect feeds the darkness of unchecked collagen. By denying proper moisture you invite the very scar you fear. Let the silicone sheet drape like a veil, and watch the horror recede.

It is essential to approach abrasion management with a systematic protocol that integrates cleansing, antimicrobial application, and controlled occlusion. Maintaining a moist wound environment minimizes desiccation, which is a known precipitant of excessive fibroblast activity. Additionally, judicious use of broad‑spectrum sunscreen after re‑epithelialization protects against post‑inflammatory hyperpigmentation. By adhering to these evidence‑based steps, practitioners can substantially reduce the likelihood of conspicuous scarring.

Yo, I get that scar talk can feel like a nightmare, but trust me, you’ve got the power to rewrite the ending. Keep that scrape clean, slather on some pet‑friendly honey if you’re into natural vibes, then toss a silicone patch on once it’s sealed. Sunshine is the enemy for fresh scars – slap on SPF like you’re armor. Stay consistent, track the progress, and you’ll see that once‑ugly mark fade into just a memory.