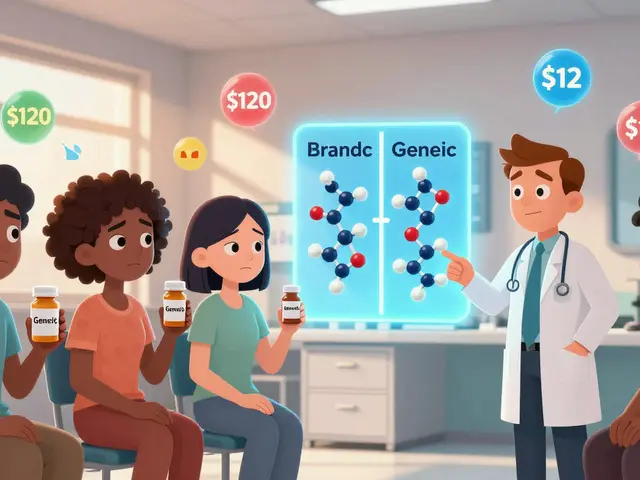

When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, the first generic version hits the market. Prices drop-sometimes by more than half. But that’s just the beginning. The real savings come when a second and then a third generic manufacturer enters the race. These aren’t just more options-they’re price smashers.

Why the second generic is a game-changer

The first generic usually cuts the brand-name price to about 87%. That sounds good, but it’s not enough to make a real difference for most patients. Then the second generic arrives. Suddenly, prices crash to around 58% of the original brand price. That’s a 30% drop in just one step. Why? Because now manufacturers are fighting for shelf space. They’re not just competing with the brand-they’re competing with each other. And in generic drug markets, price is the only thing that matters. This isn’t theory. The FDA tracked this across hundreds of drugs approved between 2018 and 2020. In every case, the second entrant triggered a sharp, measurable drop. It’s not magic-it’s basic economics. When you have two companies selling the same pill, neither can charge what they want. One undercuts the other. The other responds. The cycle continues until prices stabilize at a fraction of what they were.The third generic? It gets even worse-for drug makers

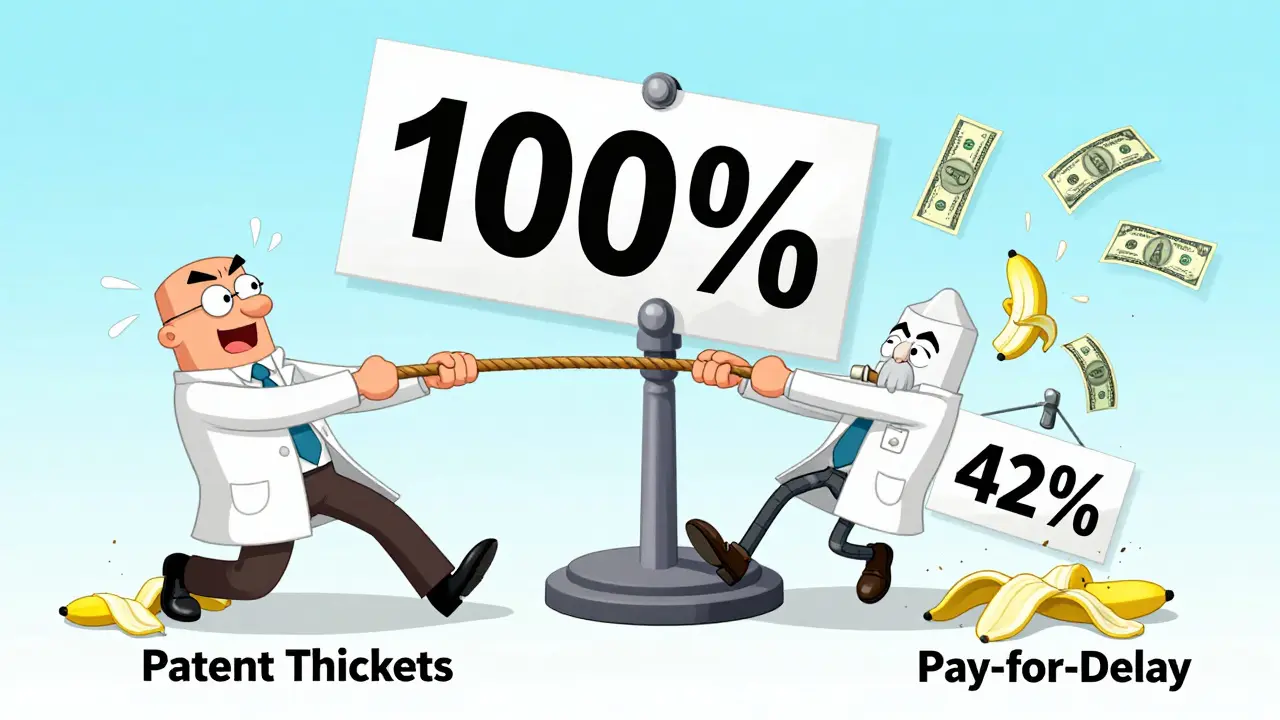

Add a third generic, and prices plunge again-to 42% of the original brand price. That’s more than a 50% drop from the first generic alone. In some markets, prices fall even lower. The data shows that with three or more competitors, drug prices often drop 60-80% compared to the brand. For patients paying out-of-pocket, that means a $300 monthly pill becomes $90. For insurers and Medicare, it means billions in savings. The numbers don’t lie. Between 2018 and 2020, 2,400 new generic drugs entered the market. Together, they saved consumers $265 billion. Most of that came from the second and third entrants. The first generic opened the door. The second and third kicked it down.What happens when competition stalls

But here’s the problem: not all markets get that far. Nearly half of all generic drugs in the U.S. end up with only two manufacturers. That’s called a duopoly. And in a duopoly, prices don’t keep falling. They often stop dropping-or even rise. A 2017 study from the University of Florida found that when a market shrinks from three competitors to two, prices can jump 100% to 300%. Why? Because without a third player to pressure them, the two remaining companies can quietly coordinate pricing. No one’s left to undercut. No one’s left to force the price down. The result? Patients pay more. And no one’s really checking. This is why the number of competitors matters more than the number of brands. One generic isn’t enough. Two is risky. Three or more? That’s when the real savings kick in.

Who’s blocking the third entrant?

You’d think more generics would mean more competition. But in reality, big players are making it harder for new ones to enter. Brand-name companies used to rely on patents to keep generics out. Now they use other tricks. One common tactic is “pay for delay”-where the brand pays a generic company to stay off the market. The Blue Cross Blue Shield Association estimates this costs patients $3 billion a year in higher out-of-pocket costs alone. Another tactic? “Patent thickets.” A single drug can have dozens of overlapping patents. One blockbuster drug had 75 patents filed to stretch its monopoly from 2016 to 2034. That’s not innovation. That’s legal obstruction. Even when generics do enter, they face a supply chain stacked against them. Three wholesalers control 85% of the market. Three pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) handle 80% of prescriptions. These middlemen have enormous power. They can favor one generic over another-not based on price, but on kickbacks or contracts. That means even if a third generic manufacturer offers the lowest price, they might not get on the formulary.Why price drops aren’t always seen at the pharmacy

You might wonder: if manufacturers are lowering prices, why do some prescriptions still cost a lot at the counter? The answer lies in the supply chain. The FDA compared two types of pricing data: what manufacturers charge (Average Manufacturer Price) and what pharmacies actually pay (wholesale invoice price). The manufacturer price dropped 60-70% with multiple generics. But the pharmacy price only dropped 40-50%. Why the gap? Wholesalers and PBMs are taking a bigger cut. This doesn’t mean generics aren’t working. It means the savings aren’t always reaching the patient. If you’re paying cash, you might still see high prices. But if you’re covered by insurance, your plan is likely saving money behind the scenes. And those savings help keep premiums lower for everyone.

Okay but let’s be real-why do I still pay $40 for a 30-day supply of metformin when the manufacturer sells it for $2? The pharmacy gets the discount, the PBM gets the kickback, and I’m left holding the bag like some kind of drug industry piñata. 🤡

And don’t even get me started on how my insurance ‘negotiates’ prices-like they’re haggling at a flea market while I’m on a fixed income. I’ve seen the same generic go from $12 to $8 to $15 in six months because some middleman decided to ‘restructure’ the formulary. It’s not capitalism. It’s a rigged game.

And yeah, third generics? Sure, they exist. But good luck finding them. My pharmacist doesn’t even know which ones are available unless I ask for them by name. And if I don’t know the name? I pay more. Again.

It’s not about competition. It’s about control. The system was designed to make you think you’re saving money while quietly siphoning it into corporate pockets. The FDA tracks prices? Cool. But they don’t track how much I actually pay at the counter. That’s the real scandal.

I’ve switched generics three times this year. Each time, the price went up. Not down. Because the ‘cheaper’ version wasn’t on my plan. The one that was? Had a $20 copay. So I paid cash. And still paid more than the actual cost of the pill. Welcome to American healthcare.

And don’t tell me ‘use GoodRx.’ I’ve tried. Sometimes it’s cheaper. Sometimes it’s not. Sometimes the pharmacy says ‘we don’t honor that.’ Sometimes they do-but only if I don’t use my insurance. So now I’m playing a 17-step game of financial Jenga just to get my blood pressure meds. And I’m not even sick. I’m just broke.

Someone needs to burn this whole system down. Or at least make the middlemen pay their fair share. But nope. We’re just supposed to be grateful that the drug isn’t $300 anymore. That’s not progress. That’s survival.

third generic drops price to 42%

but pharmacy still charges 70%

who’s stealing the rest

While the empirical data presented in this post is statistically robust-particularly the FDA’s longitudinal analysis of generic entry dynamics between 2018 and 2020-it is critically incomplete without addressing the macroeconomic implications of supply-chain concentration. The fact that three wholesalers control 85% of distribution creates a de facto oligopoly, which, per Bertrand competition theory, should theoretically drive prices downward. Yet, the observed price stagnation at the retail level suggests the presence of non-price competition mechanisms-namely, exclusive contracting and rebate structures that distort market signals.

Moreover, the CREATES Act, while well-intentioned, fails to address the root cause: the institutional capture of regulatory processes by incumbent manufacturers through lobbying expenditures exceeding $1.2 billion annually (OpenSecrets, 2023). The FDA’s GDUFA III program, while accelerating approvals, does not mandate transparency in rebate flows to PBMs. Without requiring disclosure of net prices (post-rebate), we are merely optimizing the wrong variable.

Additionally, the assertion that ‘more competitors = lower prices’ assumes perfect information and zero transaction costs. In reality, formulary placement is determined by rebate size, not unit cost. A 2021 JAMA study demonstrated that 78% of preferred generics were those offering the highest rebates-not the lowest wholesale acquisition costs.

Therefore, policy must shift from incentivizing entry to mandating price transparency. Until we can see the true net price paid by insurers, any claim of ‘savings’ is merely theatrical.

Hey everyone, I just want to say I get it. I’ve been on a generic for years and yeah, sometimes the price jumps for no reason.

But I’ve also seen the difference when a third maker comes in. Last year my cholesterol med went from $45 to $18 after another company got approved. I didn’t even know it happened until my pharmacist told me.

It’s not perfect, but it’s real. And honestly, if we all just ask for the cheapest version, pharmacies start stocking it. I used to just take whatever they gave me. Now I ask. And I’ve saved hundreds.

Also, GoodRx isn’t magic, but it’s free. And if you’re on Medicare, your plan’s savings from generics help keep your premiums down-even if you don’t see it right away.

We’re not powerless here. We just have to speak up. And maybe, just maybe, that’s enough to keep pushing things forward.

It’s funny how we call it ‘competition’ when really it’s just a race to the bottom where no one wins except the shareholders of the companies that survive

Human beings were never meant to live in a world where the price of a pill determines whether you live or die

And yet here we are

We’ve turned medicine into a spreadsheet

And we wonder why we’re so broken

OMG I JUST REALIZED MY BP MED JUST DROPPED TO $10!! 🎉 I switched to the third generic last month and my pharmacist said ‘oh yeah, this one’s new and cheap’

Also I used GoodRx and saved $25 on my thyroid med 😭

Y’all need to try this. It’s like a secret hack for surviving capitalism 🙏💸

Let’s not romanticize generics. The ‘savings’ are a myth designed to pacify the public while the real profits shift to PBMs and wholesalers. The FDA data is cherry-picked. They only track drugs with sufficient market volume. What about the 40% of generics with only one or two manufacturers? Those prices are stagnant or rising-and they’re the majority.

And don’t get me started on ‘pay for delay.’ That’s not a loophole-it’s bribery. And the fact that Congress hasn’t shut it down after 20 years proves this system is corrupt to its core.

You think you’re saving money? You’re just paying less to the same crooked machine. The only real solution is single-payer. Everything else is theater.

It is entirely unsurprising that American pharmaceutical pricing remains a grotesque parody of market efficiency. In the United Kingdom, generics are subject to strict price controls and bulk procurement. The NHS negotiates as a monopsony, ensuring that the cost of a pill is never determined by corporate whim but by public need.

Here, we have allowed the market to become a free-for-all where profit is the only metric that matters. The result is predictable: exploitation, confusion, and moral decay.

It is not the fault of the patient. It is not the fault of the pharmacist. It is the failure of governance. The U.S. government has abdicated its responsibility to protect its citizens from predatory pricing. Shameful.

There’s something quietly beautiful about how competition, even in something as cold as pharmaceuticals, can still create moments of grace.

A third manufacturer enters. A price drops. Someone breathes easier.

It’s not perfect. It’s not fair. But it’s real. And maybe that’s enough-for now.

We’re not just talking about pills. We’re talking about dignity. About people choosing between food and medicine. About the quiet, daily courage it takes to survive in a system that forgets you’re human.

So yes-push for more generics. Push for transparency. Push for change.

But also, when you see someone saving $20 on their meds today? Don’t just celebrate the number.

Celebrate the life that gets to keep going.