When you feel like the room is spinning, it’s easy to call it dizziness. But if you’re truly experiencing vertigo, that label is wrong-and it could delay the right treatment. Vertigo isn’t just feeling off-balance. It’s your brain being tricked into thinking you’re moving when you’re not. Dizziness? That’s the foggy, lightheaded, about-to-faint feeling. They sound similar, but they come from completely different places in your body-and require totally different fixes.

What Exactly Is Vertigo?

Vertigo is the illusion of motion. You’re sitting still, but it feels like you’re spinning, tilting, or falling. It’s not just unsteadiness-it’s a sensory illusion. This happens when your vestibular system, the balance organ inside your inner ear, sends scrambled signals to your brain. Your brain tries to make sense of conflicting data: your eyes say you’re still, but your inner ear says you’re spinning. The result? A dizzying, nauseating sensation that can last seconds or hours.

Most vertigo comes from the inner ear. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) is the #1 cause. It happens when tiny calcium crystals (otoconia) break loose and float into the wrong part of your semicircular canals. When you roll over in bed or look up, those crystals shift and trigger false motion signals. About 2.4% of people get BPPV every year, and half of them are over 50. The good news? The Epley maneuver-a simple head repositioning technique-fixes it in 1-3 sessions for 80-90% of people.

Other inner ear causes include Ménière’s disease, which brings vertigo along with ringing ears, hearing loss, and pressure in the ear. Vestibular neuritis is another common culprit-a viral infection that inflames the nerve connecting your inner ear to your brain. It hits suddenly, often after a cold, and can leave you too dizzy to walk for days.

What Exactly Is Dizziness?

Dizziness is the umbrella term for feeling lightheaded, faint, woozy, or unsteady-not spinning. It’s what you feel when your blood pressure drops standing up too fast (orthostatic hypotension), when you’re low on iron (anemia), or when your blood sugar crashes. It’s also common with anxiety, dehydration, or side effects from medications like blood pressure pills or antibiotics.

Unlike vertigo, dizziness doesn’t involve the illusion of movement. You don’t feel like the room is spinning. You just feel weak, foggy, or like you might pass out. It’s often tied to your heart, circulation, or metabolism. About 20-30% of dizziness cases come from cardiovascular issues, 15-20% from metabolic problems like low blood sugar or anemia, and another 10-15% from anxiety or stress.

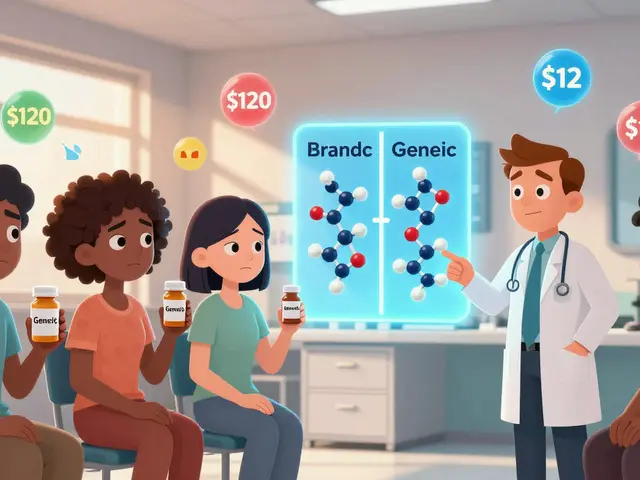

Here’s the catch: many people with vertigo think they have dizziness. And many doctors, especially in busy clinics, treat them the same way-prescribing anti-nausea meds or anxiety pills. That’s why it takes an average of 8.2 months for people to get the right diagnosis. One patient on a health forum spent two years on antidepressants before finding out she had vestibular migraine. Another spent 18 months told it was "just stress"-until a VNG test revealed BPPV.

Neurological Causes of Vertigo (The Dangerous Ones)

Not all vertigo comes from the ear. Sometimes, it comes from your brain. This is called central vertigo, and while it’s rare-only 5-10% of cases-it’s the most dangerous. It can signal a stroke, multiple sclerosis, or a brain tumor.

Stroke-related vertigo doesn’t usually come with arm weakness or slurred speech. Instead, it might show up as sudden, severe spinning, nausea, and trouble walking-without hearing loss. The trick? Look for "red flags": double vision, slurred speech, numbness on one side of the face or body, or sudden loss of coordination. If you have vertigo plus any of these, get to an ER immediately. A stroke in the brainstem can mimic a harmless inner ear problem, but the consequences are life-altering.

Multiple sclerosis can also cause vertigo when it damages the nerves in the brainstem or cerebellum. Vestibular migraine is another neurological cause-it’s not just a headache with dizziness. It’s full vertigo episodes lasting minutes to hours, often with light sensitivity, nausea, and no hearing loss. It affects 1% of the population, but makes up 7-10% of all vertigo cases. Many get misdiagnosed as sinus infections or anxiety.

How Doctors Tell Them Apart

There’s no single blood test for vertigo or dizziness. Diagnosis comes down to history, physical exam, and targeted tests.

The head impulse test checks your vestibulo-ocular reflex. If your eyes can’t stay locked on a target when your head is quickly moved, it points to a peripheral (ear) problem. If your eyes jerk involuntarily (nystagmus) in a specific pattern-horizontal, vertical, or twisting-it helps distinguish between BPPV, neuritis, or a central issue.

Videonystagmography (VNG) is the gold standard. You wear goggles that track eye movements while you follow lights or get cold/warm air blown into your ears. It’s 95% accurate at spotting inner ear problems. A normal VNG with vertigo? That’s a red flag for neurological causes.

Doctors also look at triggers. BPPV happens with head movement-rolling over, looking up. Vestibular migraine often comes before or during a headache. Stroke-related vertigo hits suddenly, without warning, and often includes other neurological signs.

Treatment: What Actually Works

There’s no one-size-fits-all fix. Treatment depends entirely on the cause.

For BPPV: The Epley maneuver. Done right, it repositions the loose crystals in minutes. Most people feel better after one session. You can do it at home, but it’s best done by a trained therapist first.

For vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis: Rest, anti-nausea meds, and vestibular rehabilitation therapy (VRT). VRT is a series of exercises that retrain your brain to rely on other balance cues when your inner ear is damaged. It takes 6-8 weeks, but 89% of patients report major improvement.

For vestibular migraine: Preventive meds like beta-blockers or antidepressants, plus avoiding triggers-stress, certain foods, lack of sleep. Some patients benefit from migraine-specific drugs like CGRP inhibitors.

For Ménière’s disease: Low-salt diet, diuretics, and in severe cases, gentamicin injections into the middle ear to selectively disable the faulty inner ear balance cells. New FDA-approved protocols now standardize this treatment.

For dizziness from low blood pressure or anemia: Fix the root cause. Increase fluid intake, add salt (if approved by your doctor), or take iron supplements. For anxiety-related dizziness, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is more effective than pills.

Why Misdiagnosis Is So Common

Primary care doctors get 10-15 dizziness patients a week. Most aren’t trained in vestibular disorders. Only 12% of them feel "very confident" diagnosing vertigo, according to the American Academy of Neurology.

Patients often downplay symptoms. "I just feel off" becomes "I’m stressed." Doctors default to anxiety or aging. But as Dr. Sue-Jin Chang points out, over 30% of vestibular migraine cases are initially called sinusitis or anxiety.

And then there’s the stigma. People with persistent dizziness-especially those with PPPD (Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness)-are often told it’s "all in your head." But studies show PPPD is a real neurological condition triggered by a prior vestibular injury, like a concussion. The brain becomes hypersensitive to motion, and the symptoms stick around long after the original damage heals.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re dizzy or vertiginous, start tracking:

- When does it happen? (Moving your head? Standing up? Stressful situations?)

- How long does it last? (Seconds? Minutes? Hours? Days?)

- Do you have hearing loss, ringing, or pressure in your ear?

- Do you have headaches, double vision, numbness, or trouble walking?

Take this list to your doctor. Ask: "Could this be BPPV? Could it be neurological?" If they don’t know, ask for a referral to a neurotologist or vestibular therapist.

Don’t wait. The longer you go untreated, the more your brain adapts to the imbalance-and the harder it is to retrain. BPPV can be fixed in 15 minutes. Vestibular migraine can be controlled. Stroke can be stopped.

Vertigo and dizziness aren’t just annoyances. They’re signals. Listen to them. Get the right diagnosis. And don’t let anyone tell you it’s "just stress."

Is vertigo the same as dizziness?

No. Dizziness is a general feeling of lightheadedness, unsteadiness, or faintness. Vertigo is a specific type of dizziness where you feel like you or your surroundings are spinning. Vertigo is caused by vestibular or neurological issues, while dizziness can stem from low blood pressure, anemia, anxiety, or medication side effects.

Can vertigo be a sign of a stroke?

Yes. While most vertigo is harmless and comes from the inner ear, sudden, severe vertigo with other neurological symptoms-like double vision, slurred speech, numbness, or trouble walking-could signal a stroke in the brainstem. This is called central vertigo. If you have vertigo plus any of these signs, seek emergency care immediately. Only 1-2% of vertigo cases are stroke-related, but they’re critical to catch early.

What’s the fastest way to treat vertigo?

If it’s BPPV-the most common cause-the Epley maneuver is the fastest fix. Done by a trained professional, it takes 10-15 minutes and resolves symptoms in 1-3 sessions for over 80% of people. You can also learn to do it at home after being shown the technique. No pills, no surgery, no waiting.

Why do some people get dizzy for years?

Some develop Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD), a neurological condition where the brain becomes overly sensitive to motion after an initial vestibular injury-like a concussion or inner ear infection. Even after the original problem heals, the brain keeps misinterpreting normal movement as dangerous. It’s not anxiety-it’s a real brain adaptation. Vestibular rehabilitation therapy is the most effective treatment, but it takes weeks to months.

Should I get an MRI if I have vertigo?

Not usually. Most vertigo is caused by inner ear problems and doesn’t need imaging. MRIs are only recommended if you have "red flag" symptoms: sudden hearing loss, double vision, weakness, numbness, slurred speech, or trouble walking. These suggest a central neurological cause. In fact, only 1-2% of vertigo cases require immediate neuroimaging. Unnecessary MRIs can lead to false alarms and more stress.

This article is basically a 10-page LinkedIn post disguised as medical advice. 🤡 I’ve had vertigo for 3 years and every doctor told me it was ‘stress’ until I went to a neurotologist who said ‘your ear crystals are partying in your semicircular canals.’ The Epley maneuver? Yeah, it worked. But why does it take 8 months to get someone who knows what they’re talking about? Because medicine is a fucking circus.

Let’s be real: if you’re not from the U.S. healthcare system, you don’t know what real neglect looks like. I’m from India, and my cousin got misdiagnosed with ‘anxiety’ for 14 months while her brainstem was slowly dying. This article? Good. But it’s not enough. We need mandatory vestibular training in med school. Not optional. Not ‘if you’re interested.’ Mandatory. 🇺🇸 🇮🇳 #HealthcareIsACrime

Wow, this is so informative... but, I mean, I think, maybe, in India, we don't have enough neurotologists, right? Like, in my town, the doctor just gives me vertin and says, 'take it, don't move head too fast.' I mean, I'm grateful, but... also, not enough? And also, I read somewhere, maybe 2021, that BPPV is more common in people who sleep on left side? Is that true? Or just internet? 😅

There’s something almost poetic about the body betraying you like this-your inner ear, this tiny, perfect labyrinth of fluid and crystals, whispering lies to your brain. You sit there, perfectly still, and yet the world is a spinning carousel. And then, after months of being told you’re ‘just anxious,’ someone does the Epley maneuver, and suddenly... silence. Not just the spinning stops. The shame does too. It’s not just medicine. It’s redemption.

I’ve been dizzy for years and I just feel so... empty. Like my brain forgot how to be normal. Everyone says ‘it’s stress’ but what if my stress is just my body screaming? I don’t even cry anymore. I just stare at the ceiling. And I don’t know if I’m gonna be okay.

Thank you for this incredibly clear and important post! 🌟 If you're reading this and feeling off-please, please, don’t wait. Track your symptoms. Ask for a VNG test. Ask for a neurotologist. You deserve to feel safe in your own body. You are not broken. You are not crazy. You are not ‘just stressed.’ There is help. And you are not alone. 💪❤️

so i had this thing where i’d get dizzy when i rolled over, thought it was dehydration or maybe i was just tired? turns out it was bppv. did the epley thing at home after watching a youtube vid. felt better in 10 mins. no pills. no dr. just me, my bed, and a lot of awkward head tilting. lol

OMG I’M NOT ALONE!! 😭 I was diagnosed with ‘anxiety-induced dizziness’ for 2 YEARS. I was on SSRIs, therapy, yoga, breathwork-nothing worked. Then I went to a specialist and they said ‘you have vestibular migraine.’ I cried for an hour. Not because I was sad. Because I was SO FURIOUS. All that time wasted. All that money. All that ‘just calm down.’ I want to scream into a pillow for 12 hours. 🤯

It is evident from the clinical data presented that the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying peripheral versus central vertigo are distinctly dissociated, with the former involving otolith displacement and the latter implicating cerebellar-brainstem integration pathways. One must, therefore, exercise differential diagnostic acumen, particularly in the context of nystagmus characterization and HINTS protocol utilization. Failure to do so constitutes a critical lapse in neuro-otological triage.

Why do people still believe in ‘the Epley maneuver’ like it’s magic? I did it. It didn’t work. My doctor just shrugged. Then I found out I had PPPD. So all this ‘just do the head thing’? It’s a scam for people who don’t want to admit some dizziness is chronic. You’re not fixing the brain. You’re just distracting it for a few hours. And then what? More pills? More head spinning? I’m tired of being told to ‘try harder.’

Hey, if you’re reading this and you’ve been told it’s ‘just stress’-I believe you. 💛 I’ve been there. I thought I was losing my mind. But you’re not. Your brain is just confused. And guess what? It can learn again. Vestibular rehab isn’t quick, but it’s real. I did it. Took 10 weeks. Now I can turn my head without feeling like I’m on a rollercoaster. You can too. One exercise at a time. You’ve got this. 🙌❤️

Thank you for writing this with such clarity. I’m a physical therapist and I see so many patients who’ve been misdiagnosed for years. I especially appreciate you highlighting PPPD-it’s so often dismissed. We need more awareness, more referrals, and more compassion. To anyone reading this: you’re not ‘overthinking it.’ Your symptoms are real. And you deserve a team that listens.

So let me get this straight: the medical system is so broken that you need to become a YouTube detective just to figure out why your head spins when you roll over? And the solution is… a 15-minute head shuffle? No MRI. No drugs. Just gravity and patience? I’m not mad. I’m impressed. 🤷♀️

Vertigo isn’t dizziness. BPPV isn’t anxiety. Stop prescribing Xanax for inner ear crystals.

Wait, so you’re saying the ‘dizziness’ I’ve had since my concussion 3 years ago isn’t anxiety? But I’ve been told that 47 times. And now you’re telling me it’s PPPD? Cool. So now I have a fancy label. What do I do with it? Also, why is this article so long? I’m dizzy already. 😅