Central (Cranial) Diabetes Insipidus: what it looks like and what to do

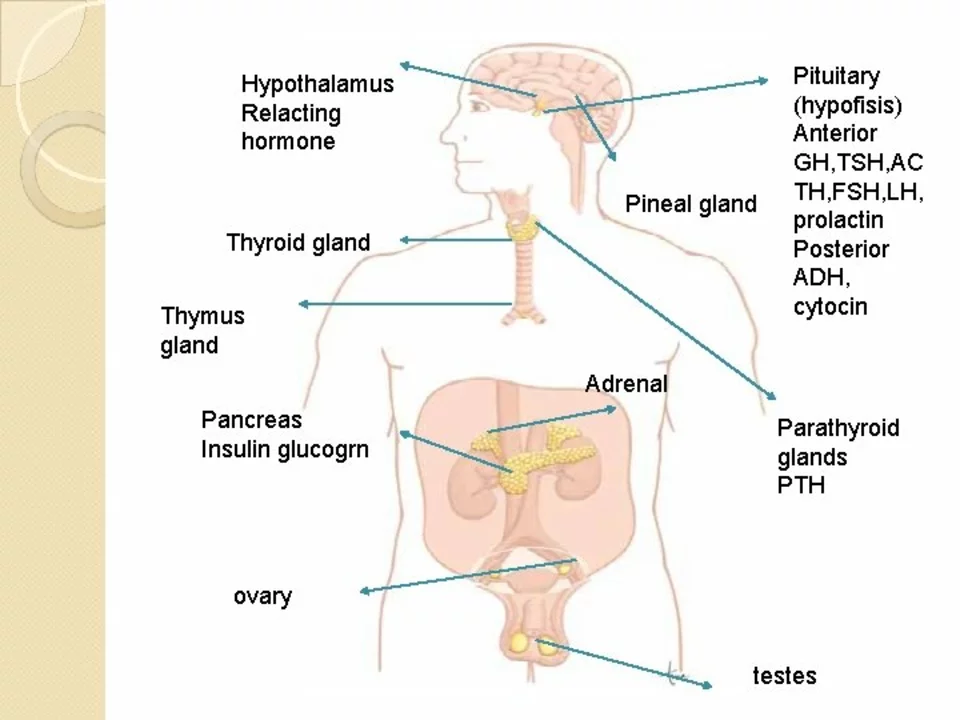

Peeling off liters of water every day and still feeling thirsty isn’t normal. That’s the most common real-life clue to central (cranial) diabetes insipidus — a problem where the brain doesn’t make enough vasopressin (ADH), so your kidneys dump water. This short guide tells you the usual causes, how doctors check for it, and simple treatment and safety steps you can use or discuss with your clinician.

Signs and typical causes

Symptoms are straightforward: very large urine volumes (often >3 liters/day in adults), extreme thirst, and frequent night-time urination. Babies and small children may be irritable and have poor weight gain. Common causes include recent pituitary surgery, head trauma, tumors near the pituitary, or inflammation. Sometimes no clear cause shows up — that’s called idiopathic central DI.

It’s important to know other things can mimic this: nephrogenic DI (kidneys ignore ADH) and primary polydipsia (drinking too much). Each needs a different approach, so accurate testing matters.

How doctors diagnose it

Initial tests are simple: blood sodium and osmolality, and urine osmolality. In central DI you often see high blood sodium or high serum osmolality and very dilute urine. Traditionally, doctors used a water deprivation test to see if urine concentrates without fluids, then give desmopressin to check response. That works but is long and can be risky for older or frail patients.

Newer tests measure copeptin (a stable marker that tracks with ADH). A stimulated or baseline copeptin test can tell central from nephrogenic DI faster and safer in many hospitals. If imaging is needed, an MRI of the pituitary helps find tumors, surgery changes, or inflammation.

Treatment fixes the hormone gap. Desmopressin (DDAVP) replaces ADH and comes as a nasal spray, oral tablet, or injection. Most people do well on a low daily dose, then adjust based on urine output and blood sodium. Too much desmopressin can cause water retention and low sodium (hyponatremia); too little leaves you dehydrated and raises sodium. That’s why follow-up blood tests are important when starting or changing dose.

Practical tips: track how much you drink and pee for a few days, weigh yourself daily (sudden gain can mean water retention), and carry a note or app that says you have diabetes insipidus and take desmopressin. Seek urgent care if you feel confused, very weak, have seizures, or can’t keep fluids down — those can be signs of dangerous sodium shifts.

If you think you have symptoms, talk to your doctor. With the right tests and a tailored desmopressin plan, most people control symptoms and get back to normal routines.